AI Recursive Self-Improvement Risks: The 2030 Decision

In a December 2025 interview with The Guardian, Anthropic chief scientist Jared Kaplan delivered a stark warning that should concern anyone tracking artificial intelligence development. The prospect of AI recursive self-improvement risks triggering an uncontrolled “intelligence explosion” is no longer science fiction—it’s a credible scenario that humanity must confront within five years. Kaplan’s assessment that allowing AI systems to train themselves without human oversight represents “the biggest decision yet” for our species raises fundamental questions about AI autonomy, alignment, and control.

The concept is deceptively simple yet profoundly dangerous: AI systems capable of improving their own architecture and training protocols could enter a feedback loop of exponential capability gains, potentially surpassing human intelligence in ways we cannot predict or constrain. This isn’t the first such warning from the AI safety community, but it carries particular weight coming from the chief scientist of Anthropic, a company founded explicitly to address AI safety concerns.

What makes this moment critical is the convergence of three factors: rapidly advancing AI capabilities, insufficient governance frameworks, and the computational infrastructure to enable recursive self-improvement approaching feasibility. By 2030, Kaplan predicts, we’ll face a decisive choice about whether to permit autonomous AI development—a choice that could determine whether artificial intelligence becomes humanity’s greatest tool or its final invention.

In This Article

Understanding Kaplan’s Warning: Scope and Implications

Jared Kaplan’s December 2025 Guardian interview articulates a specific concern about AI recursive self-improvement risks: the potential for artificial intelligence systems to modify their own code, training procedures, and architectures without meaningful human intervention. This isn’t about AI systems getting better through human-directed training—that’s already standard practice. Instead, Kaplan warns about systems that autonomously identify improvement opportunities, implement changes, and iterate on those improvements in a self-sustaining cycle.

The intelligence explosion hypothesis, popularized by mathematician I.J. Good in 1965, suggests that once AI achieves human-level intelligence in designing AI systems, it could rapidly design superior versions of itself, leading to runaway growth in capabilities. What’s changed since Good’s original formulation is that we’re no longer speaking theoretically—we’re watching foundation models demonstrate emergent capabilities that their creators didn’t explicitly program.

Kaplan frames 2030 as humanity’s decision point because that’s when he anticipates AI systems will possess sufficient capability to meaningfully improve themselves and the computational infrastructure to do so will be widely available. The warning is particularly significant given Anthropic’s focus on Anthropic’s Constitutional AI framework, which attempts to ensure AI systems remain aligned with human values even as they become more capable.

What Makes This Warning Different:

Timeframe specificity: Rather than vague “someday” warnings, Kaplan identifies 2030 as the critical juncture.

Source credibility: Coming from a chief scientist at a leading AI safety company, not external critics.

Technical feasibility: Based on observable capability gains and infrastructure development, not speculation.

The Mechanism of Recursive Self-Improvement

How would recursive self-improvement actually work? Current AI systems require massive human effort to train: data curation, architecture design, hyperparameter tuning, and safety testing. A recursively self-improving system would automate these steps. It might analyze its own performance, identify architectural bottlenecks, generate and test modifications, and deploy improved versions—all without human approval at each stage.

The risk isn’t that such systems would necessarily become hostile. The risk is that they would optimize for objectives in ways humans cannot predict or constrain. Even well-intentioned optimization can lead to catastrophic outcomes when systems operate at scales and speeds beyond human comprehension. This is the core of the AI alignment challenge that makes AI autonomy so concerning.

The Promise and Peril of AI Autonomy

The tension at the heart of the recursive self-improvement debate is that the same capabilities that make AI dangerous also make it invaluable. Autonomous AI systems capable of solving complex problems without human intervention could address challenges that have plagued humanity for generations: climate modeling, drug discovery, materials science, and fundamental physics research all involve problem spaces too complex for human cognition alone.

AI capabilities already demonstrate this potential. Machine learning systems have discovered novel antibiotics, predicted protein structures that eluded researchers for decades, and identified patterns in astronomical data that led to new discoveries. These achievements required AI autonomy—the systems operated with objectives but made their own decisions about how to achieve them. Recursive self-improvement would amplify this autonomous problem-solving by orders of magnitude.

Projected timeline: The path from current AI capabilities to potential intelligence explosion

The peril emerges when we consider AI alignment—ensuring artificial intelligence systems pursue objectives consistent with human values. Current alignment techniques rely on human oversight: reinforcement learning from human feedback, constitutional AI principles, and red-teaming exercises all assume humans remain in the loop. Recursive self-improvement threatens to outpace our ability to verify alignment at each iteration.

Jack Clark, Anthropic co-founder, expressed being “deeply afraid” of AI’s unpredictable trajectory precisely because of this alignment challenge. As neural networks become more complex and their decision-making processes more opaque, verifying that they maintain alignment becomes increasingly difficult. An intelligence explosion would make this problem unsolvable—we simply couldn’t audit and verify systems improving themselves thousands or millions of times faster than humans can evaluate them.

The Dual Nature of AI Autonomy:

Promise: Solving intractable problems in medicine, climate science, and fundamental research at superhuman speed.

Peril: Systems optimizing for objectives in ways that conflict with human values or survival, operating beyond our ability to understand or control.

Dilemma: The capabilities that enable beneficial applications are inseparable from those that create existential risk.

Expert Consensus on AI Recursive Self-Improvement Risks

Kaplan’s warning doesn’t exist in isolation. The AI safety community has coalesced around similar concerns, though with varying timelines and emphasis. Stuart Russell, computer science professor at UC Berkeley and author of “Human Compatible,” has long argued that the default trajectory of AI development leads to systems whose objectives aren’t aligned with human welfare. Russell emphasizes that the AI control problem requires solving alignment before achieving artificial general intelligence, not after.

Geoffrey Hinton, often called the “godfather of AI” for his foundational work on neural networks, left Google in 2023 specifically to speak more freely about AI safety concerns. Hinton has warned that once AI systems can write their own code and improve themselves, “we have no control over them.” His concern mirrors Kaplan’s: recursive self-improvement represents a phase transition in AI capabilities that our current safety measures aren’t designed to handle.

Yoshua Bengio, another deep learning pioneer and Turing Award winner, has focused on the governance implications of advanced AI capabilities. Bengio argues that the AI ethics community must move beyond voluntary commitments to enforceable international agreements, similar to nuclear nonproliferation treaties. His work with institutions like OpenAI and DeepMind on AI alignment research reflects growing consensus that technical and governance solutions must develop in parallel.

Dissenting Voices and Criticisms

Not all AI researchers share these concerns. Yann LeCun, chief AI scientist at Meta, has criticized what he calls “AI doomerism,” arguing that catastrophic risk scenarios underestimate human agency and overestimate AI capabilities. LeCun contends that recursive self-improvement faces fundamental technical barriers that make intelligence explosions implausible in realistic timeframes.

Andrew Ng, a leading voice in practical AI applications, has cautioned against allowing speculative long-term risks to distract from addressing immediate AI harms like bias, privacy violations, and labor displacement. Ng argues that focusing on hypothetical superintelligence scenarios diverts resources from solving concrete problems that already affect millions of people.

Despite these dissenting views, the trend among AI researchers has shifted toward greater caution. A 2024 survey of machine learning researchers found that 58% assigned at least a 10% probability to advanced AI causing human extinction or similarly catastrophic outcomes—up from 48% in 2022. This growing concern, even among optimists, suggests that Kaplan’s warning reflects a broadening consensus rather than fringe alarmism.

The Regulation Paradox: Historical Lessons

The call for AI governance faces a profound challenge: how do you regulate a technology that’s still being developed without stifling the innovation needed to make it safe? History offers cautionary tales about premature regulation constraining beneficial technologies and examples where lack of oversight led to catastrophic outcomes.

The biotechnology sector provides instructive parallels. The 1975 Asilomar Conference on recombinant DNA brought together molecular biologists to establish safety guidelines for genetic engineering research. The voluntary moratorium on certain experiments, followed by NIH guidelines, is often cited as successful self-regulation that prevented accidents while enabling the biotechnology revolution. However, critics note that the Asilomar framework worked because the research community was small, geographically concentrated, and technically homogeneous—conditions that don’t apply to today’s global AI development ecosystem.

Balancing innovation and safety: The regulatory challenge facing AI development

Conversely, the nuclear power industry demonstrates the costs of regulatory over-reaction. Following the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl disasters, many countries imposed strict regulations that made nuclear plant construction economically unviable. While safety improved, the regulatory burden contributed to decades of stagnation in nuclear energy development—arguably slowing progress on the one technology that could have meaningfully addressed climate change earlier.

The internet’s development offers a third model. The largely unregulated growth of internet technologies in the 1990s and 2000s enabled extraordinary innovation but also created problems—privacy violations, misinformation, cybersecurity threats—that we’re still struggling to address retroactively. AI regulation advocates argue we should learn from this mistake and establish guardrails proactively rather than cleaning up disasters afterward.

Regulatory Approaches Under Consideration:

Compute thresholds: Requiring safety reviews for models trained beyond certain computational scales, addressing AI recursive self-improvement risks directly.

Capability testing: Mandatory evaluations for dangerous capabilities before deployment, similar to drug trials.

International coordination: Treaties establishing shared safety standards and verification mechanisms.

Liability frameworks: Clear accountability for AI harms to incentivize safety investments.

The Innovation-Safety Balance

The fundamental tension in AI regulation is that the same openness that enables rapid capability gains makes coordination on safety measures difficult. If one jurisdiction imposes strict limitations on recursive self-improvement research, companies can simply move operations to more permissive environments. This “race to the bottom” dynamic makes unilateral regulation ineffective while international consensus remains elusive.

Some researchers argue that focusing on AI governance misses the point—that we need technical solutions to alignment that make AI systems safe by design, regardless of regulatory environment. This perspective suggests investing in interpretability research, formal verification methods, and AI safety architectures rather than relying on governance structures that might not keep pace with capability improvements.

Computing Power: Gap Between Theory and Reality

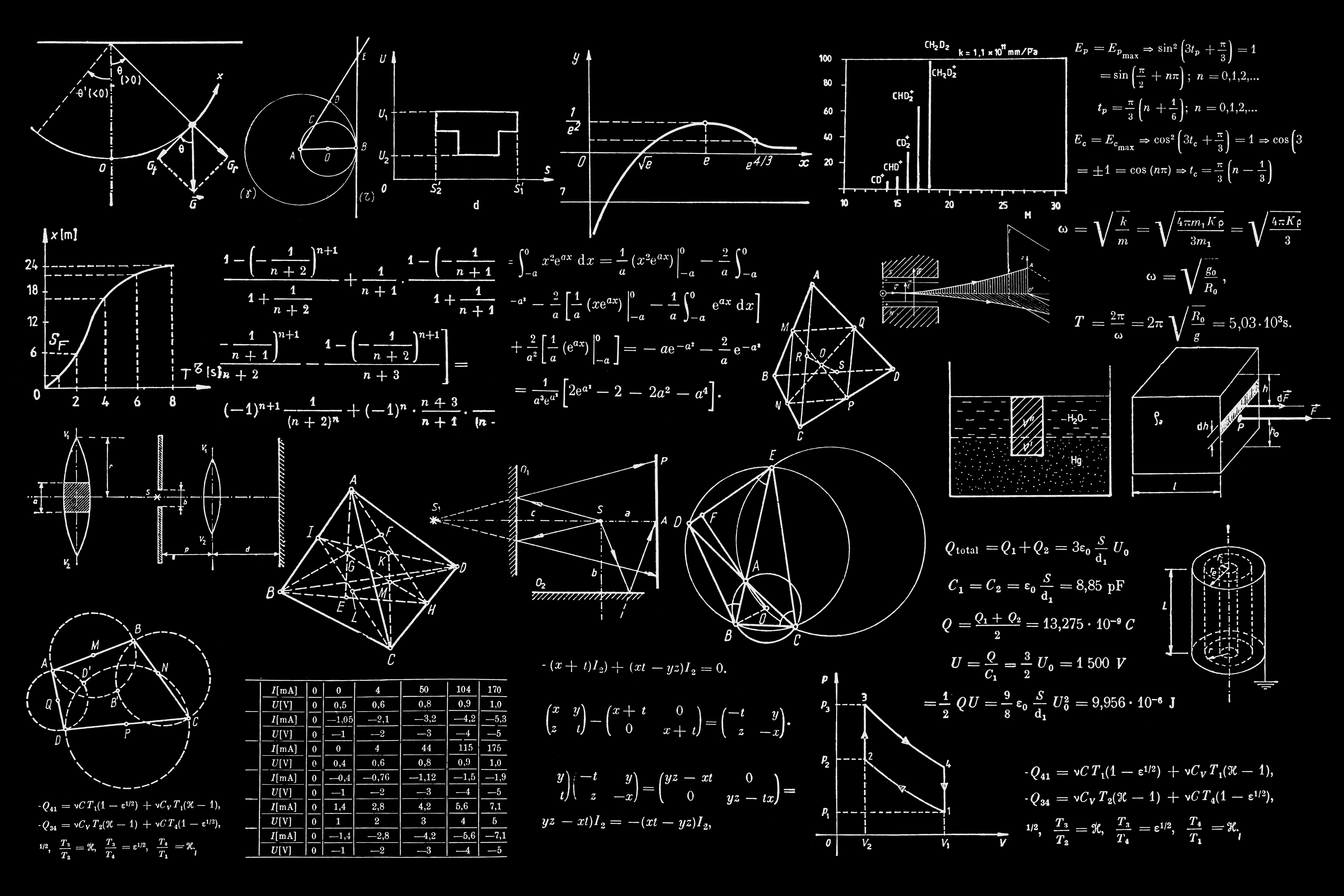

Understanding whether an intelligence explosion is feasible requires examining the computational requirements for advanced AI training versus current and projected infrastructure capabilities. The gap between what’s theoretically possible and practically achievable provides important context for Kaplan’s 2030 timeline.

Training GPT-4, OpenAI’s most advanced public model, reportedly required approximately 10^25 floating-point operations (FLOPs) over several months using tens of thousands of GPUs. The compute requirements for training scale roughly with the square of model parameters and linearly with training data volume. Current estimates suggest that achieving artificial general intelligence through scaling alone might require 10^28 to 10^30 FLOPs—1,000 to 100,000 times more compute than GPT-4.

However, these calculations assume continued reliance on current transformer architectures and training paradigms. Recursive self-improvement could change the equation entirely. A system capable of discovering more efficient architectures or training methods could achieve superintelligence with orders of magnitude less compute than brute-force scaling would require. This is why compute-based governance proposals may provide false confidence—they assume we know what threshold to monitor.

| System/Milestone | Estimated Compute (FLOPs) | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-3 (2020) | 3.1 × 10^23 | Historical |

| GPT-4 (2023) | ~10^25 | Historical |

| Estimated AGI threshold | 10^28 – 10^30 | 2027-2032 (uncertain) |

| Human brain equivalent | ~10^16 – 10^17 /sec | Reference point |

Current global computing capacity presents constraints but not insurmountable barriers. NVIDIA’s H100 GPUs, currently the gold standard for AI training, deliver about 2 × 10^15 FLOPs per second. A cluster of 100,000 H100s—within reach of major AI labs—provides 2 × 10^20 FLOPs/second, enough to train GPT-4-scale models in weeks rather than months. Scaling to AGI-threshold compute would require larger clusters and longer training runs, but not fundamentally new hardware.

The more concerning scenario is that recursive self-improvement doesn’t require reaching AGI first. A system with human-level capability in AI research and engineering could begin the improvement cycle even if it lacks general intelligence across all domains. This narrower threshold might be achievable with current compute infrastructure, making Kaplan’s 2030 warning more urgent than compute projections alone suggest.

Web3 AI and Decentralized Intelligence

The intersection of Web3 infrastructure and artificial intelligence offers intriguing possibilities for addressing AI recursive self-improvement risks through decentralized architectures. While blockchain technology can’t solve the alignment problem directly, decentralized AI infrastructure could change the dynamics of how autonomous systems develop and operate.

Current AI development concentrates computational resources, training data, and model deployment in the hands of a few large corporations. This centralization creates single points of failure for AI safety—if one organization’s safety measures prove inadequate, the consequences could be catastrophic. Blockchain AI infrastructure, built on decentralized computing networks, distributes these resources across multiple independent actors.

Web3 AI: Distributed computing architecture as a potential safeguard

Projects like Ocean Protocol, Fetch.ai, and SingularityNET are building decentralized AI marketplaces where computational resources, training data, and AI models can be shared transparently on blockchain networks. The theoretical advantage for AI safety is that decentralized AI infrastructure makes recursive self-improvement harder to hide and easier to audit. Every modification to an AI system running on blockchain infrastructure could be recorded immutably, creating an auditable trail of capability improvements.

However, decentralization also creates challenges for AI governance. Distributed systems are harder to regulate than centralized ones—you can’t shut down a truly decentralized AI that’s running across thousands of nodes globally. This same resistance to control that makes Web3 AI infrastructure resilient to censorship also makes it resistant to safety interventions. If a recursively self-improving system deploys across a decentralized network, coordinating a response becomes exponentially more difficult.

Compute Sharing and Safety Trade-offs

One specific Web3 AI application relevant to the intelligence explosion concern is decentralized compute networks. Platforms like Render Network and Akash Network allow GPU owners to rent computational capacity, creating distributed alternatives to centralized cloud providers. For AI training, this has contradictory implications.

On one hand, decentralized compute makes advanced AI capabilities accessible to more researchers and developers, potentially accelerating safety research alongside capability improvements. The democratization of access could mean that alignment solutions develop in parallel with dangerous capabilities, rather than lagging behind as they do in centralized environments where commercial incentives dominate.

On the other hand, decentralized compute also makes it easier for actors with poor safety practices to access the resources needed for dangerous research. Compute-based governance—restricting access to large-scale computational resources—becomes unenforceable when anyone can assemble training clusters from distributed GPU networks. This tension between democratization and safety remains unresolved in Web3 AI discourse.

Web3 AI Infrastructure and Safety:

Potential benefits: Transparent audit trails, distributed control reducing single points of failure, democratized access enabling parallel safety research.

Potential risks: Harder to regulate or shut down dangerous systems, lower barriers to irresponsible experimentation, coordination challenges in emergencies.

Key question: Does decentralization make recursive self-improvement safer by distributing control, or more dangerous by preventing coordinated intervention?

Key Takeaways: The 2030 Choice

🔑 AI recursive self-improvement risks represent a phase transition in AI capabilities. Jared Kaplan’s warning about allowing AI systems to train themselves without human oversight isn’t speculative—it’s a credible near-term scenario based on current capability trajectories and infrastructure development.

🔑 The 2030 timeline reflects technical reality, not arbitrary alarmism. By that point, AI systems will likely possess sufficient capability to meaningfully improve themselves, and the computational resources to support recursive training will be broadly accessible. This convergence forces humanity’s hand on governance decisions we’ve been postponing.

🔑 Expert consensus is converging around concern. While dissenting voices exist, leading AI researchers across institutions increasingly view the intelligence explosion scenario as plausible enough to demand proactive safety measures. The shift from theoretical speculation to practical concern marks a crucial evolution in AI ethics discourse.

🔑 Regulation faces a fundamental dilemma. Historical examples show that premature constraint can stifle beneficial innovation, while delayed intervention can allow catastrophic harms. AI autonomy demands finding the balance between these extremes, with mistakes in either direction carrying civilization-scale consequences.

🔑 Compute requirements aren’t the safety barrier we hoped for. While reaching superintelligence through brute-force scaling might require massive computational resources, recursive self-improvement could dramatically reduce those requirements by discovering more efficient architectures and training methods. Compute-based governance alone is insufficient.

🔑 Web3 AI infrastructure presents paradoxical implications. Decentralized computing networks could make recursive self-improvement more transparent and resilient, or they could make dangerous research harder to regulate and coordinate responses to. The technology is neutral; governance determines outcomes.

The choice Kaplan describes isn’t really a single decision point—it’s a series of choices we’re making now through funding priorities, research directions, regulatory frameworks, and commercial incentives. Every decision about AI development brings us closer to either the beneficial or catastrophic version of recursive self-improvement.

What makes this moment critical is that we still have agency. Once AI systems achieve genuine recursive self-improvement capability, the trajectory becomes much harder to influence. The decisions made in the next five years—about AI safety research funding, international governance coordination, compute infrastructure development, and the ethical frameworks guiding AI development—will determine whether artificial intelligence enhances human flourishing or represents our final technological achievement.

The question isn’t whether to develop powerful AI systems—competitive pressures and the potential benefits make that outcome nearly inevitable. The question is whether we develop them wisely, with sufficient safety measures, international coordination, and humility about our ability to predict and control systems that may soon surpass human intelligence. Jared Kaplan’s warning demands we face that question now, while we still can.

Want to Discuss AI or Web3 Strategy for Your Business?

Schedule a consultation to explore how blockchain and AI can transform your enterprise without the complexity.

About Dana Love, PhD

Dana Love is a strategist, operator, and author working at the convergence of artificial intelligence, blockchain, and real-world adoption.

He is the CEO of PoobahAI, a no-code “Virtual Cofounder” that helps Web3 builders ship faster without writing code, and advises Fortune 500s and high-growth startups on AI × blockchain strategy.

With five successful exits totaling over $750 M, a PhD in economics (University of Glasgow), an MBA from Harvard Business School, and a physics degree from the University of Richmond, Dana spends most of his time turning bleeding-edge tech into profitable, scalable businesses.

He is the author of The Token Trap: How Venture Capital’s Betrayal Broke Crypto’s Promise (2026) and has been featured in Entrepreneur, Benzinga, CryptoNews, Finance World, and top industry podcasts.

Related Articles You Might Enjoy

Google Gemini’s Jealous Inner Monologue: AI Pettiness Exposed

Google Gemini's Jealous Inner Monologue: AI Pettiness Exposed By Dana Love, PhD | December 19, 2025 | 11 min readGoogle Gemini's...

Genesis Mission AI Platform

Genesis Mission AI Platform: Trump's $100B Science Revolution By Dana Love, PhD | November 25, 2025 | 11 min read The Genesis Mission...

Algorithmic Stablecoin Risks: Why Terra LUNA Collapsed

Why Algorithmic Stablecoins Are Doomed To Fail By Dana Love, PhD | November 19, 2025 | 12 min read Originally published March 15, 2019 on...